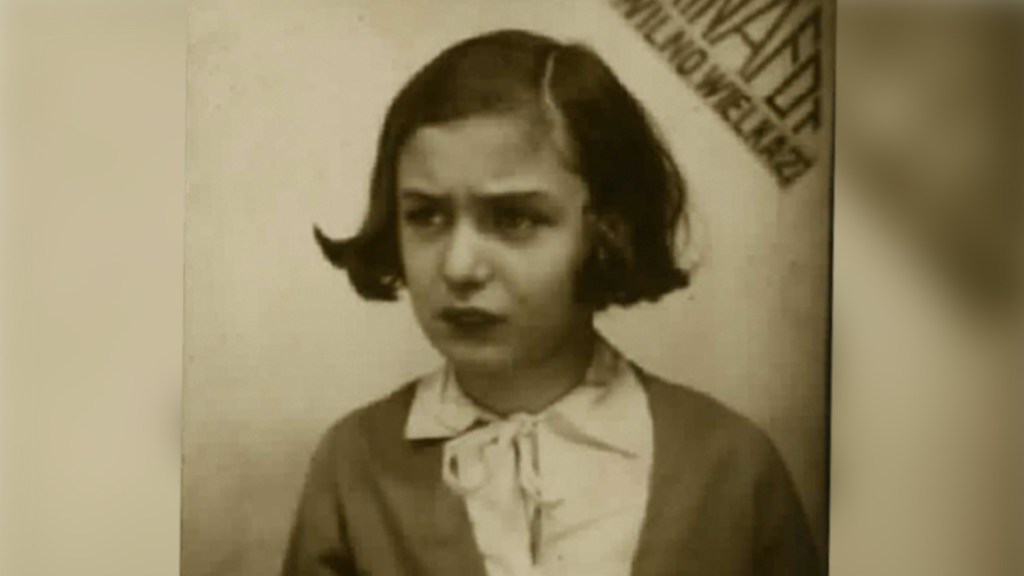

Before her world disappeared into the horrors of the Holocaust, fifth-grader Beba Epstein wrote about her life in pre-World War II Poland, describing summers in the countryside, an outing to watch the movie "Uncle Tom’s Cabin" in her hometown of Vilna, a religious grandfather who never smiled and a grandmother who was "a great storyteller."

“One thing for sure — I was a big brat,” she wrote in that essay, composed during the 1933-'34 school year at the Sofia Gurevich school in what is now Lithuania.

She got into mischief at home, sending dishes crashing to the floor from a sideboard when she was 2 and ripping her cousin’s neatly copied geography assignment to bits, but also grew into a keen if sometimes unsparing chronicler of her secular, middle-class life. She described working late into the night on school work but also the illnesses that forced her to miss class and the deprivations that her parents suffered during the First World War.

“I speak Polish and Yiddish, but I prefer to read in Yiddish,” she wrote. “I learned to write very quickly!”

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, "The Autobiography of Beba Epstein" was lost along with thousands of documents once held at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in Vilna.

Part of the collection was destroyed, part was taken by the Nazis to Frankfurt for a planned anti-Semitic institute, but another cache of material, including her memoir, remained forgotten until 2017. That is when some 170,000 pages of material was discovered.

They had been smuggled out of the YIVO building into the Vilna ghetto by Jews who made up what was known as the “Paper Brigade." The material was later dug up and then concealed in various places by librarian Antanas Ulpis. He hid some in the Church of St. George, which was converted by the Soviets into the National Lithuanian Book Chamber and is now the Martynas Mażvydas National Library of Lithuania, and some in the Wroblewski Library. All are in what is now Vilnius.

"The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Girl”

Today the child’s essay is at the heart of the first interactive exhibit of an online museum created by YIVO, which began reassembling its collection after it relocated to New York in 1940. The notebook remains in the library in Lithuania, but the virtual display, the start of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum, becomes a jumping off point for an exploration of Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

Designed by the museum’s chief curator, Karolina Ziulkoski, “Beba Epstein: The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Girl” draws on YIVO’s more than 23 million documents and artifacts and on the University of California, Los Angeles' Holocaust Testimonies Project, done in cooperation with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Beba Epstein: the Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Girl | Short Trailer from YIVO Online Museum on Vimeo.

As YIVO, founded in Vilna in 1925, considered how to highlight material in online exhibitions, Ziulkoski thought to focus on individuals whose lives could be told through the artifacts in the archives. Beba Epstein was an appealing way to reach other children.

“What struck a chord with me with her story is that given the refugee situation in the world right now, you can see that her life was not unlike the lives of many kids today,” Ziulkoski said. “There is a lot to connect with kids today.”

Beba, who was born in 1922, quarreled with her siblings, was a good student in school, ice skated in the winter and swam in the summer. She went to summer camp.

“I am very loved at home, but they don’t spoil me — only when I’m sick — then I get special privileges,” she wrote.

Her mother, Malke, suffered during the First World War, Beba wrote, when the food the Germans provided was inedible and her brothers and father were arrested and detained for days. Her father, Shimen, was sent off to Turkestan and Tashkent for his military service and then was drafted for the First World War.

“He took every precaution to avoid being taken prisoner because the Germans tortured their prisoners,” she wrote. “He was in huge battles where tens of thousands perished and where cities and towns were burned to the ground.”

Jerusalem of the North

Jews made up 40% of Vilna’s population at the time, and the city was known as the “Jerusalem of the North,” a center for the Jewish Enlightenment with more than 100 synagogues and places of study. Some Jews were religious, others secular, some embraced the promise of Zionism and a new life in Palestine, others devoted themselves to socialism or communism. Children attended a variety of schools, including Polish public schools, and in the summers, families headed to resorts and to summer camps.

Accompanying her story are others written in the 1930s for contests sponsored by YIVO and collected in “Awakening Lives: Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland Before the Holocaust.” More than 600 were submitted, showing the variety of the young people’s experiences, though only about half survived the destruction of World War II.

“I’ve heard that they used to eat with silver spoons,” a 22-year-old unemployed glass factory worker wrote of his father’s wealthy family. A member of a Zionist youth group who had tried unsuccessfully to emigrate to Palestine, he lived in poverty, often with little to eat and his father’s earnings going to doctors.

Another young man, a 20-year-old who was a member of the socialist party, wrote, “My mother tells me that on the day I started to learn to walk, the Bolsheviks arrived. It was a beautiful day, and I was taking my first steps, chasing a rooster around the yard. Just then a hail of shrapnel and bullets rained down on our town, striking all the roofs with a great crash.”

The collection is rich in photographs, film clips, maps and historical artifacts. The musical prodigy Jascha Heifetz, a Vilna native, appears in a portrait as a child playing the violin in 1908. Police report on Jewish revolutionaries when Vilna was part of the Russian empire in 1899 to 1900, while a notice details the theft of cows from the old age home in the 1920s. A card from 1939 celebrates Rosh Hashanah or the new year.

Anti-Semitism Surges in US, Elsewhere

Jonathan Brent, YIVO’s executive director, has long wanted to make YIVO's collection more accessible to people around the world. The project to digitize it and recreate as much of the pre-war archives and library as possible began in 2015, but with documents in Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, German and Lithuanian, translating 1.5 million pages for a general audience was not feasible, so the idea of a museum was born, he said.

“Through these documents you learn about actual lives, actual communities,” he told a United Nations conference on combatting anti-Semitism last year.

They bring alive social, political and religious conflicts, the books people read and the movies they saw, their school assignments and their ambitions and "the religious aspirations of the communities that had existed for hundreds and hundreds of years," he said.

Putting the material online is especially important as anti-Semitism flares up in the United States and elsewhere. The Anti-Defamation League's annual tracking of anti-Semitism showed more incidents in 2019 than in any other year, up 12% over the year before. They included three deadly assaults: by a white supremacist on the Chabad of Poway, California; on a grocery store in Jersey City, New Jersey; and at a Hanukkah party at the home of a rabbi in Monsey, New York.

Anti-Semitism is at the core of the white supremacist ideology, and helps to fuel other forms of hate, including Islamophobia and misogyny, said Vlad Khaykin, the ADL's national director of programs on anti-Semitism.

To combat anti-Semitism, it is key to show the diversity among Jews, whether race, color, class or background and also experience with anti-Semitism, he said.

“When you treat Jews as a monolith, it makes it a lot easier to stereotype Jews,” he said.

Beba Epstein's account can open up the lost world of the prewar Jewish community, said the Lithuanian ambassador to the United Nations, Audra Plepyte.

That it is online is important to teach young people in particular, a counter-narrative to the anti-Semitism on the internet, she said.

"One small document can be a source of inspiration,” she said.

When Beba Epstein’s autobiography was discovered in 2017, many people, among them Brent, assumed she had died in the Holocaust. But then The New York Times wrote about the find and featured Beba’s photograph and with that came a call from a Michael Leventhal of Los Angeles, California.

"We looked at it and we were like, 'Oh my God,'" Leventhal said.

That is because Beba Epstein was his mother. Not only had she survived but she had made way to an uncle in America, had married another émigré from Poland, Elias Lee Leventhal, and had made a home in Pacific Palisades, California. She earned a bachelor’s degree when she was 58, and became a social worker for Jewish Family Services welcoming new immigrants, many of them Jews from the Soviet Union, until she was about 70.

She loved Chopin and Mozart and was incredibly proud of Jascha Heifetz, the musician. "He was from Vilna, you know," Leventhal said at her memorial service.

But his mother struggled to be happy, to appreciate the life she made with her husband for her children. He son used to tell her, “There was a group of people who tried to kill you over 60 years ago. You’re still here, and they’re all gone. And look what you’ve created.”

When Vilna was invaded by the Germans, and the city’s Jews were confined to a ghetto, her family sent her to live at a farmhouse in the countryside. She could pass for Polish, she said later for an interview for the University of California, Los Angeles, Holocaust Testimonies Project. But when she lost touch with her family, she was smuggled into the ghetto to find that all of them — her parents, her sister, Esye, a piano player and dancer, a brother Mote who loved horses, the youngest, Khayeml, whom in the autobiography she had described as chubby and adorable and just learning to talk — had perished.

Surviving the Holocaust, Saving Herself

Beba Epstein went on to survive two years in the ghetto and another two years in labor camps, including the Kaiserwald concentration camp and the Stutthof extermination camp. She cleaned for the Gestapo and worked in a munitions plant and surreptitiously listened to the radio for the underground.

When she was finally freed, after a harrowing trip on a ship during which her cousin drowned, she had typhoid and weighed 74 pounds. She recovered in Sweden and eventually found an uncle in the United States with the help of The Forward newspaper. It published names of survivors which were read aloud in Israel, and a friend of the uncle happened to hear hers.

“Her experience during the Holocaust was so unique,” Ziulkoski said. “She didn't have a savior. She essentially saved herself. She went through this by herself."

"She was hidden with a family, she was in the ghetto, she was in concentration camps, the whole of different experiences in one person’s life," she said.

Rachel Knopfler, a teacher at the Girls Academic Leadership Academy in Los Angeles, will use the material with her seventh-grade English students, the autobiography and the primary sources accompanying it.

Knopfler, whose grandmother and great-grandmother survived the Holocaust together in Auschwitz-Birkenau, said she wished she had been introduced to the period through something like Beba Epstein's writings rather than as she was, through horrifying pictures and stories. The YIVO exhibit is accurate, relies on primary documents, but is not traumatizing, she said.

“Teaching the Holocaust is not about shock value,” she said. “What we're doing is we’re teaching tolerance.”

That is especially important now, given today’s resurgence of anti-Semitism, the Proud Boys chanting “Jews will not replace us,” in Charlottesville, Virginia, last year, and the U.S. Capitol rioter, Robert Keith Packer of Newport News, Virginia, wearing a “Camp Auschwitz” shirt. Too many young people are becoming desensitized to the Holocaust, which makes the photograph of Packer so vile and scary, Knopfler said.

Khaykin, a refugee himself from the former Soviet Union, said one fear is that anti-Semitism will become cool and so the ADL is looking at ways to fight back against viral videos on TikTok and elsewhere. He said he was not surprised that anti-Semitism was on the rise, but was dismayed that political leaders were not speaking out more forcefully.

“It is incumbent on them to use their bully pulpit to push back,” he said.

Robert Sandler teaches a course on Jewish history at Stuyvesant High School in New York City. In other years, he would have taken his students on a walking tour of the Lower East Side of Manhattan, once an enclave for Jewish immigrants, and to visit YIVO and the exhibits on display there. This year they instead visited pre-war Vilna virtually.

Later he asked his students which chapters of Beba Epstein's life they would chose to most engage other teenagers. Jewish, Catholic and Muslims, as diverse as New York City, some of them immigrants themselves, they juxtaposed the material about her life and the monstrosity of the Holocaust, the streetscape of Vilna and Jewish communities around the world with the ghettos and death camps.

That her essay has been published online now, after the Trump administration closed doors to refugees, was particularly well-timed, her son said.

View Beba Leventhal's oral testimony of the Holocaust later in her life through the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum here.

“That’s something that directly bears on my mothers’s life experience,” he said. “The idea that maybe there’s a lesson to be learned there and that she would be part of that lesson would be something that I think would thrill her.”

Beba Epstein's grandson Noah Leventhal wrote about reading her autobiography after she had died. He had not known her whole story while she was alive. He was missing the child's perspective the essay offered.

"And now I have been gifted a book, a book through which to peer into the life of someone I thought I knew. Each new perspective came with the turn of a page, an experience I hope my readers will share. I wish I could have spoken to my grandmother, not the woman she was after she came out of the war, but the little girl she was before it started."