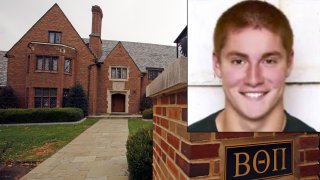

Hazing in New Jersey will be met with harsher penalties under a new law named after Tim Piazza, a state native and Penn State student who died in 2017.

Gov. Phil Murphy signed Timothy J. Piazza's Law on Tuesday at Raritan Valley Community College, not far from where Piazza, who died when he was a 19-year-old sophomore studying engineering, grew up. Pennsylvania also enacted tougher anti-hazing laws in 2018 that permit fraternity houses to be confiscated when severe hazing occurs.

“Hazing will no longer be treated with a symbolic smack on the back of the hand or, worse, a blind eye and a smirk," said Murphy.

Jim and Evelyn Piazza, Tim's parents, who have become anti-hazing advocates since their son's death, joined Murphy, who gave them each a pen he used to sign the bill.

Get top local stories in Philly delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC Philadelphia's News Headlines newsletter.

New Jersey's and neighboring Pennsylvania's laws are the strongest in the country against hazing, the Piazzas said.

The measure requires all public and private middle and high schools, as well as colleges and universities, to draw up anti-hazing policies, along with penalties for violations that could include withholding of a diploma, suspension or expulsion.

The new law also establishes that hazing resulting in serious injury or death will be considered a third-degree crime, up from a fourth-degree. A conviction will carry a prison sentence of up to five years, a fine as high as $15,000, or both. That's increased from a prison term of up to 18 months, a $10,000 fine or both.

U.S. & World

Stories that affect your life across the U.S. and around the world.

The law also increases hazing that results in injury from a disorderly persons offense with a penalty of as much as six months of prison time and a $1,000 fine, or both, to a fourth-degree crime.

Before Tuesday, New Jersey law generally described hazing as “conduct, other than competitive athletic events, which places or may place another person in danger of bodily injury.”

The new law broadens the kinds of activities that can be considered hazing to include actions that cause or coerce someone to violate the law, to consume food or drink that can put the person at risk of physical or emotional harm, or to endure physical or mental brutality, along with any other kind of activity that could hurt the person.

Republican state Sen. Kip Bateman sponsored the legislation after hearing from 12-year-old Matthew Prager, Piazza's neighbor and friend, who wrote to Bateman asking him to author anti-hazing legislation in Piazza's memory.

“To this day, I am grateful to Matthew for sending me that letter. No student deserves to go through the ritual humiliation that 19-year-old Timothy Piazza experienced on the night that he lost his life," Bateman said.

Evelyn Piazza praised Prager for advocating for the new law.

“If a 12-year-old boy can recognize the difference between what is right and wrong and what it means to be a friend and inclusive, we are hopeful others can learn from this," she said.

Piazza died after getting drunk and falling several times on a night in February 2017 while seeking to join the Beta Theta Pi fraternity.

Investigators concluded Piazza had had at least 18 drinks in under two hours. A security system recorded much of what happened before and after he fell down basement steps, had to be carried back upstairs, and spent the evening and ensuing night on a first-floor couch, showing signs of severe pain.

Piazza suffered severe head and abdominal injuries, but help was not summoned until the next morning. He died at a hospital.

His death prompted Penn State to ban the fraternity, and Pennsylvania state lawmakers to pass legislation making the most severe forms of hazing a felony, requiring schools to maintain policies to combat hazing and allowing the confiscation of frat houses where hazing has occurred.