Constance Wilson is angry. She’s angry that her grandson is no longer with her. She’s angry that his accused killers still haven’t been convicted. And she’s angry at Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner for the role that she believes he played in delaying justice for her family.

“I don’t trust him,” she said. “He put the same people back on the street.”

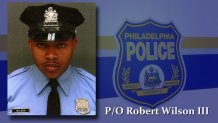

Her grandson, Philadelphia Police Sgt. Robert Wilson III, visited a North Philadelphia GameStop on March 5, 2015, to buy a video game for his son. Two gunmen entered the store and announced a holdup. Wilson tried to thwart the robbery and died after a shootout with the suspects.

More than three years after Wilson’s death, Constance Wilson is still waiting for the men accused of killing him to go to trial. Both Carlton Hipps and Ramone Williams are charged with murder, conspiracy, robbery and a long list of related charges.

Last month, the accused men's defense team asked a Philadelphia judge for additional time to prepare their case. Prosecutors did not oppose the request and a new pretrial hearing was set for June with a two-week jury trial expected to start in November.

The delay outraged Wilson’s family.

"What good is he doing?"

That question triggers dramatically different answers depending on who you ask. And it’s a question that Krasner answered himself during an interview with NBC10 as he reflected on his first 100 days in office.

During his campaign for district attorney, Krasner promised to change the system by reducing mass incarceration, to fight corruption by bringing transparency to his office and to battle injustice by ending cash bail for low-level offenders.

But several families of victims question whether Krasner's crusade interferes with his duties as the city's chief prosecutor, the top official in charge of punishing crime.

Krasner argues that his continued commitment to social reform is, in fact, the most effective way to fight crime.

"We have to be willing to be smart, not just political, when it comes to crime,” he said.

Being smart, according to the district attorney, includes investing money into education and drug and mental health treatment rather than placing people in jail for non-violent offenses.

“The 16-year-old who is still in school is not the one who is most likely to go pick up a gun and go kill somebody,” he said.

U.S. & World

Stories that affect your life across the U.S. and around the world.

When asked if the artwork was recently displayed for the commemoration of King's death, Krasner's spokesman, Ben Waxman, answered simply: "They're always there."

Born in 1961 in St. Louis, Missouri, to a World War II veteran father and a Christian minister mother, Krasner attended public school in Philadelphia. He received his Bachelor of the Arts from the University of Chicago and then attended Stanford Law School, where he focused on indigenous rights, homelessness and poverty. After graduating in 1987, he returned to Philadelphia and became a public defender.

In 1993, Krasner opened his own law practice in Center City that specialized in criminal defense and civil rights. He sued the Philadelphia Police Department more than 75 times on corruption and physical abuse charges. His reputation as a social justice activist was one reason for Krasner's 75 percent margin of victory in last year’s closely watched district attorney race.

Krasner vowed to bring sweeping reforms and transparency to an office plagued by the scandal surrounding former District Attorney Seth Williams, who was convicted on corruption charges and sentenced to prison time.

He wasted no time reshaping the 600-person-strong office. More than 30 staff members were either fired or resigned within three days of Krasner's tenure.

He also implemented new policies, including ending cash bail for low-level offenders, requiring prosecutors to reveal the cost of incarceration before sentencing and dropping criminal charges on 50 marijuana possession cases. Those policies, he said, were part of a larger goal to end mass incarceration.

In March, a leaked memo showed Krasner instructing prosecutors to stop charging for "any amount" of marijuana possession and some cases of prostitution.

Krasner's policies drew national headlines and praise from left-leaning progressives — as well as criticism from hard-liners who labeled him an enabler of criminals.

But speaking to NBC10, Krasner emphatically rejected the notion that he was soft on crime.

“Come on now — the criticism you’re repeating is coming from people whose administration had a higher rate of violent crime last year than we have right now,” he said.

Despite his reputation as an impassioned reformer, Krasner is calm and composed in person, already comfortable in the media spotlight having drawn the attention of prominent leaders throughout the country.

At the mention of Gerard Grandzol, however, he choked back tears.

The 38-year-old community activist was shot and killed in front of his 2-year-old daughter in September. Krasner described Grandzol’s "horrifying" murder as an "absolutely crushing tragedy."

The accused shooter was 16 years old at the time of Grandzol’s death. In March, the suspect’s defense attorney requested that he be tried in juvenile court.

Grandzol’s widow and family supporters pleaded for Krasner to prevent that from happening.

Yet despite his personal opposition to the death penalty, Krasner's office said in March that the case remained a capital one at that time. It is currently under review by a committee that will determine the most appropriate sentence to seek. That committee will send Krasner their recommendation and he will make a decision, though it won’t be a political one, Krasner said.

"I have a duty here that I will complete," he said. "But there’s nothing inconsistent about pursuing your duty and having a personal opinion that the death penalty is a bad thing."

Krasner is part of a current wave of elected officials nationwide who are rethinking the ways their offices pursue justice. At the beginning of 2017, New Jersey essentially ended cash bail, a move that Krasner implemented here in February. He argued that requiring people to post bail for minor crimes — like driving under the influence and retail theft — unfairly targets those who can’t afford to pay to keep themselves out of jail.

John Hollway, the executive director of Penn Law's Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, said Krasner is embracing a “21st-century role of prosecutors as crime reducers.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, the prevailing trend for law enforcement was based on the so-called "broken windows theory" developed by two criminologists. The theory is that stemming the rise of minor crimes, from subway turnstile jumping to burglary, could lead to suppression of more violent crime.

The approach evolved following decades of police departments, including Philadelphia’s under police commissioner and Mayor Frank Rizzo, aggressively hunting criminals and pursuing tough prison sentences.

Now, however, the theory has been criticized, and lawmakers such as Krasner are taking a more holistic approach by focusing on the big picture before sending offenders to jail.

Some people, the thinking goes, could be better served through social services than prison time.

"If you’re going to send somebody away for two years, it should be worth it," Krasner said. "If you’re going to send them away for 50 years ... it should be worth it."

This can seem counterintuitive to victims of crime who want to see harsher forms of justice.

“It’s a very natural, emotional reaction to want to punish people for committing crimes,” Hollway said. “Sometimes an eye for an eye seems just. The question is whether incarcerating somebody will reduce crime.”

Krasner doesn’t necessarily believe so, which is why he is now requiring prosecutors to reveal the cost of sending an offender to prison during sentencing. The policy, Krasner argued, actually supports victims because it reveals "the social cost" of a crime and helps focus resources on violent offenses.

It's too soon to tell whether his reforms will change Philadelphia's criminal justice system.

From July 2015 to December 2017, Philadelphia’s jail population decreased 25 percent, according to the city’s Office of Criminal Justice. Officials attribute that success to policies rolled out after Philadelphia received a $3.5 million grant from the MacArthur Foundation in 2016. The money went towards decreasing reliance on cash bail, implementing police diversion programs and providing early bail review for pretrial defendants, among other initiatives.

Since Krasner took office, the jail population fell 9 percent. It is currently hovering around 5,500, according to the city's Office of Criminal Justice.

"This could be attributable to a number of factors, including new policies and initiatives across the city’s criminal justice system," Julie Wertheimer, from the Office of Criminal Justice, said.

Like the prison population, Philadelphia’s homicide rate is down from this time last year. Philadelphia Police Capt. Sekou Kinebrew, the department's spokesman, credits many things “working in tandem,” such as building a better relationship between communities and law enforcement. That relationship extends to the district attorney’s office. Kinebrew told NBC10 he speaks with Krasner’s staff at least once a week.

Yet one of Krasner’s harshest critics is Fraternal Order of Police President John McNesby, who labeled the district attorney as "anti-police."

After Krasner spoke to cadets about the use of unnecessary force, McNesby accused him of endangering the lives of officers through his “ridiculous and dangerous presentation.” The statement was refuted by Krasner’s spokesman in a series of tweets.

McNesby did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.

During his interview with NBC10, Krasner denied being at odds with law enforcement, saying he has an "excellent relationship" with Philadelphia Police Commissioner Richard Ross. He also cited his efforts to keep more officers on the street.

Kinebrew confirmed that Ross and Krasner have met, and that the two offices continue to work closely together.

Yet the anti-police accusations leveled against Krasner have been bolstered by the recent criticisms from Sgt. Wilson’s family. Not only did they accuse him of slowing down the murder case, they also questioned his previous relationship with Michael Coard, a defense attorney for one of the suspects and a member of Krasner’s transition team.

The district attorney’s spokesperson said that Coard and Krasner have not spoken about the case since he took office.

“Let’s understand, [the case is] three years old,” Krasner said. “The prior administration had all those other years and they did not succeed at getting it to trial despite all the chest-beating.”

Krasner added that his office will be careful to not go to trial unprepared, which could lead to a case being overturned. He also insisted that he met with Wilson’s family members personally to speak with them.

Ultimately, Krasner believes the impact of his social reform will lead to justice for Wilson, Grandzol and other victims of violent crime.

“We have to do things that actually work," the district attorney said, "not just talk tough.”

Krasner’s activist approach to crime reduction is ambitious. It’s long-term effectiveness remains to be seen, however, and will not only define his legacy, but also Philadelphia’s future.

“What he’s trying to do is really exciting and really difficult,” John Hollway from the Quattrone Center said. “He’s trying to improve and modify the culture. Not just the district attorney’s office but the entire criminal justice system. To the law enforcement side, he has to show that he can protect.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correctly reflect the status of the Wilson case in March. It was a capital case at that time, Krasner's office said.