When Becky Schwarz saw the message in her patient portal saying she could no longer receive a prescription for methotrexate to treat her lupus, she felt surprised. It was only six days after the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade, the landmark case that guaranteed the constitutional right to abortion, and she was already feeling the impact. The drug helps her manage the autoimmune condition’s flares, which include pain, exhaustion and rash.

“I am a 27-year-old woman. I am fully educated about what’s best for me and for my body,” the Northern Virginia resident told TODAY. “The frustrating thing is you start to feel like you’re being babysat. Why am I not capable of taking care of myself?”

The health care system that her doctor practices under made the decision to pause prescribing methotrexate because it can be used to end a pregnancy, and the organization wanted to make sure their new, post-Roe policy would not expose providers to any legal consequences, according to the message, which TODAY reviewed.

(In Virginia, abortion is legal until the end of the second trimester and in the third to protect the health of the mother, but Gov. Glenn Youngkin has recently been advocating for a 15-week ban, NBC affiliate WWBT reported.)

Get top local stories in Philly delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC Philadelphia's News Headlines newsletter.

“It was a large overcorrection,” Schwarz said. “I was surprised by how quickly it happened.”

She shared her thoughts in a tweet that went viral. Schwarz hoped to help others understand how far-reaching she believes the Supreme Court decision is.

“I really wanted to educate some of the people in my life who knew me personally to see that Roe wasn’t just there to make abortion legal,” Schwarz said. “(It) protected the right to unrestrained health care for women.”

Patients report struggling to receive medication

Schwarz is not alone. Dr. Kenneth Saag, president of American College of Rheumatology (ACR), told TODAY that he's heard reports of other patients with lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis having a difficult time obtaining methotrexate. On social media, numerous people who say they use methotrexate have shared stories about challenges getting their prescriptions filled and concerns about future access to the drug. (TODAY has not independently verified these claims.)

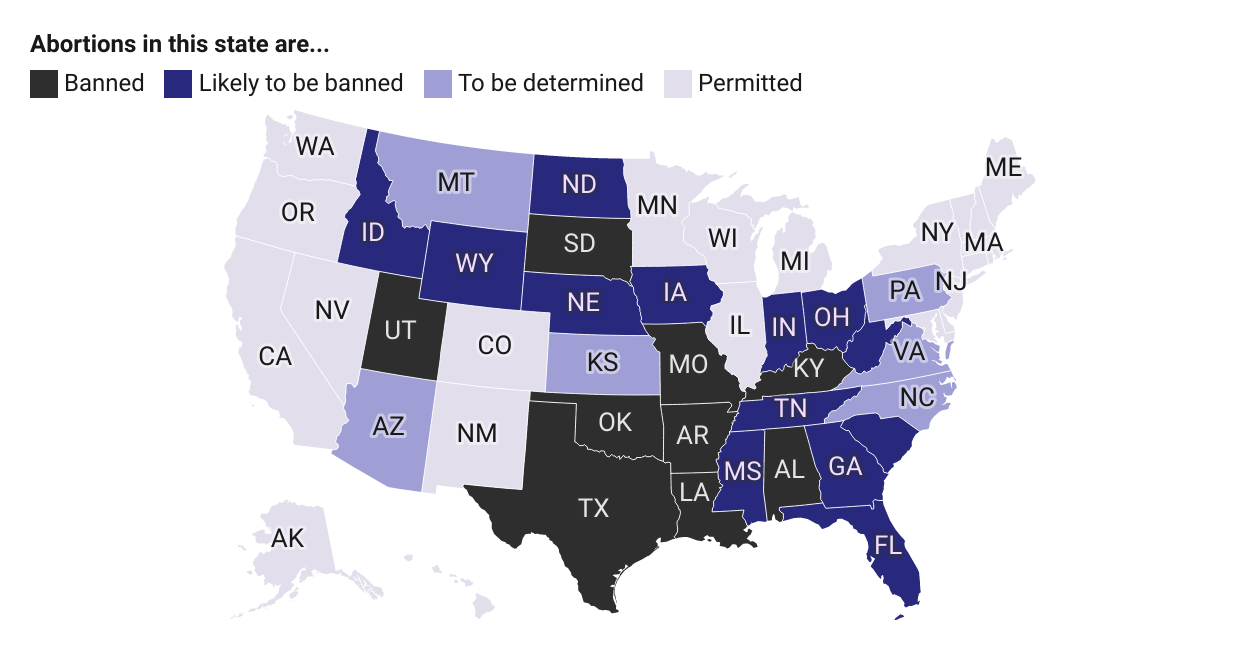

Earlier this week, medical journal BMJ published an article asserting that "patients are reporting trouble accessing drugs for autoimmune diseases in light of some US states banning abortion inducing drugs."

“The American College of Rheumatology is quite concerned about this,” Saag said. “We’ve got a lot of people on a very effective medicine who may now have limited access to it due to concerns, particularly by pharmacists, and we need ultimately to clarify policy and to make sure patients continue to have unfettered access to medicines.”

The drug has been used by rheumatologists since the 1980s to reduce inflammation for several autoimmune disorders, Saag said. But it can cause birth defects, according to 2014 research from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, and it's also commonly used to treat ectopic pregnancy, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

“There’s always somewhat unanticipated consequences of changes to government policies, and regrettably I think a lot of pharmacists, a lot of physicians are uncertain about the implications of this new decision by the Supreme Court," Saag said.

The ACR also shared a statement with TODAY that reads, in part:

“The ACR is aware of the emerging concerns surrounding access to needed treatments such as methotrexate after the recent decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. We are following this issue closely to determine if rheumatology providers and patients are experiencing any widespread difficulty accessing methotrexate, or if any initial disruptions are potentially temporary and due to the independent actions of pharmacists trying to figure out what is and isn’t allowed where they practice."

"The ACR has assembled a task force of medical and policy experts to determine the best course of action for ensuring our patients keep access to treatments they need."

What is methotrexate?

Methotrexate was first used to treat some cancers at higher doses, but in smaller doses, it reduces inflammation in conditions such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and some childhood arthritis, Saag said.

“The doses are much, much lower,” Saag explained. “People take it weekly. There is a pill or a shot they can give themselves, and generally, it’s very well tolerated.”

“It’s a remarkably effective medicine and really one that we rely on substantially," he continued. "A third and maybe in some practices up to half of these patients are taking this medication. ... It costs less than $100 typically a month.”

Methotrexate “can actually extend life expectancy," Saag added.

“It suppresses inflammation in various parts of the body when autoimmune conditions, like rheumatoid arthritis, attack the joints or in the case of psoriasis attack the skin,” he said. “(It has) a really impressive improvement in the way people feel and its potential for extending their lives. … Poorly treated rheumatoid arthritis can shorten your life expectancy by 10 or more years.”

But the drug can impact pregnancies.

“(Birth defects are) a relatively uncommon problem (with methotrexate),” Saag said. “If a woman is on the medicine and somehow does get pregnant, unfortunately then it’s about a 10% or less likelihood that the child will have a problem. But it is obviously a significant problem.”

That’s why many doctors who prescribe methotrexate talk with their patients about managing this risk, Saag said.

“For women of childbearing potential, we have a discussion about the need for adequate birth control,” he said. “(We discuss) the need to stop the medicine. The recommendation is optimally for several menstrual cycles before attempting to get pregnant. And that’s a very deliberate discussion that we, as arthritis healthcare professionals, have to minimize risk of exposure."

Autoimmune conditions can impact people of any age, gender and race, but women experience them "at a rate of 2 to 1," according to a 2020 paper in the journal Cureus.

Saag said he worries that not being able to get methotrexate will "affect (patients') quality of life."

"You have people that have been on this medicine for years and years and are doing very well, and all of a sudden they don’t have access to the drug anymore,” Saag said.

The ACR is trying to work with politicians so future laws benefit patients, Saag said: “We have a concerted effort to talk to members of the House and Senate and other health care regulators to make sure that the policies are in the best interest of the patients and allow rheumatologists … to practice as well as they can and have the ability to work with their patients to individualize their care."

The impact on patients

For Schwarz, the policy change means that she will need to be weaned off the drug sooner than she and her doctor had planned, she said. Because she's had to switch from methotrexate to another medication before, she has an idea of what to expect.

“There is always going to be increased disease activity just as you’re transitioning meds because my immune system doesn’t know how to process much,” Schwarz said. “I did have some pretty extreme nausea as I was changing.”

And this time around could be "harder," Schwarz said, as she'll need to be weaned off the drug more quickly than last time because of her doctor's office's new policy on methotrexate. She’s been working with her rheumatologist to plan as best she can.

“She told me to prepare myself for a pretty significant flare,” Schwarz said, using the term for periods when lupus symptoms become more severe. “With that comes again a lot of the pain and the immobility. I can’t go outside in the sun.” (The Lupus Foundation of America estimates that 40% to 70% of people with lupus experience worse symptoms after UV exposure.)

As tough as this situation is for Schwarz, she also feels for her doctor.

“I love her. I believe fully that she’s advocating for me as much as she is capable of within the role she has,” Schwarz said. “I’m safer for having her be my rheumatologist than if she were to lose her job by giving me a medication she isn’t allowed to give.”

This story first appeared on TODAY.com. More from TODAY: