Thousands of pounds of deadly hydrofluoric acid escaped into the atmosphere following the massive June 21 blast at the now-shuttered gas refinery in South Philadelphia, according to a new federal report.

More than 5,200 pounds of the chemical, known shorthand as HF, was estimated to have been released from a complex system of pipes in three early morning blasts, the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board said in its finding released Wednesday.

The root cause of the explosions? A decades-old elbow pipe had degraded to just 7 percent of thickness level, the federal safety agency said. That is well-below the threshold that normally would prompt replacement.

"The thickness of this elbow was not monitored," the board wrote in the report.

The escape of the deadly HF has not been previously confirmed by investigatory authorities. A Reuters article published in August first raised the possibility that HF may have been released in the blasts, but city and company officials would not confirm the report at the time.

The report said 676,000 pounds, in total, of hydrocarbon chemicals are estimated to have escaped containment in the disaster. A large majority of those chemicals was gas products, which burned during the explosions and subsequent fire.

HF can be very painful, and lethal, when it comes in contact with humans, and even a small leak could lead to a widespread catastrophe, particularly in a heavily-populated area like South Philadelphia.

However, widespread effects weren't reported in the hours and days that followed the explosion at Philadelphia Energy Solutions' refinery.

That would suggest the thousands of pounds of HF that did escape were likely thrown high into the atmosphere during the powerful blasts, leaked very slowly in low concentration, or both, according to Peter DeCarlo, an air quality expert and Drexel University professor.

"That's a massive release," DeCarlo said. "Based on what we've seen and based on the lack of major health impacts, which would have been clearly observed, we dodged a fairly substantial bullet."

The refinery was the largest on the East Coast, and was Philadelphia's largest polluter for decades. Its origins as an industrial site go back two centuries.

The current owner, PES, filed for bankruptcy in July. It was the second time in two years that the company did so. Protests by South Philadelphia residents and some city leaders followed the explosion, with calls for a shutdown of the facility. About 300 union workers were laid off in August. The facility employed about 1,000.

The fire burned for two days until plant staff were able to turn off a valve that sent fuel into the alkylation unit where the degraded pipe initially burst. City fire officials and the refinery's private fire brigade let the fire burn to avoid the uncontrolled release of explosive gas into the atmosphere.

U.S. & World

Stories that affect your life across the U.S. and around the world.

Philadelphia Fire Department Commissioner Adam Thiel said most of the fuel burned was similar to what fuels gas barbecue grills.

Even after the fire was extinguished, the disaster site wasn't ruled officially contained until September.

A minute-by-minute leadup to the explosions that NBC10 ran live on its early morning newscasts is included in the report and show how quickly the catastrophe developed inside one of the HF alkylation units of the refinery:

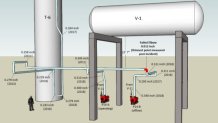

- At 4 a.m., there was a sudden loss of containment that caused flammable process fluid, including HF, to release into the unit. It formed a "ground-hugging vapor cloud."

- At 4:02 a.m., the vapor cloud ignited, causing a large fire in the alkylation unit.

- Thirty seconds later, a control room operator activated the Rapid Acid Deinventory system.

- At 4:15 a.m., during the still-burning fire, the first of three explosions occurred. The second explosion occurred four minutes later.

- At 4:22 a.m., the third and largest blast occurred when a feed drum within the alkylation unit "violently ruptured." The drum contained combustible gases, primarily butylene, isobutane and butane. Butane is known for its use in cigarette lighters.

A fragment of the drum, which weighed nearly 20 tons, was ejected and flew across the Schuylkill River. Two other fragments, about 11 and eight tons each, also went airborne. They landed elsewhere in the refinery. A federal investigator called their landing spots "miraculous" for not damaging other parts of the facility as they came back to earth.

The likelihood that the HF released during the explosions went high into the atmosphere instead of escaping at low levels into nearby neighborhoods was also very fortunate, DeCarlo, the air quality expert, and federal officials said.

"We are aware that Hydrogen Fluoride (HF) was released into the atmosphere during the June 21 explosion/fire," Mayor Jim Kenney's spokeswoman, Deana Gamble, said in a statement Wednesday. "According to PES, the estimated amount represents less than 1% of the HF inventory in the damaged unit before the incident started. HF was not detected in the air by multiple agencies and the City believes that the public was in no immediate danger from HF during the fire and response."

However, DeCarlo testified before a state legislative oversight committee in July that an inspector with Philadelphia's Air Management Services agency did register a positive reading for HF on a monitoring device. His testimony was first reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Gamble said in an email that the device was found to be miscalibrated, and other air quality readings performed by PES and the Environmental Protection Agency found no HF in the area surrounding the refinery.

"Due to the meter not being properly calibrated, the inspectors requested that the EPA and PES confirm the zero readings. Both confirmed that there was no HF present in the community, and the (Air Management Services) inspectors took the improperly calibrated meter out of service," Gamble wrote. "AMS subsequently confirmed with the manufacturer that the handheld device was in fact in need of recalibration and was thus unreliable when used immediately after the fire. Unified Command was also confident in its decision to shelter in place based on safety protocols that were executed successfully. Ultimately, the City believes that the public was in no immediate danger from HF during the fire and response."