Editor’s Note: NBC10 spoke with three sets of parents plus several lawmakers, advocates and medical experts for this story. All of the parents requested pseudonyms for either themselves or their children.

Rather than attend school as a teenage girl, 13-year-old Chris binds his breasts to avoid confusion. He is proud presenting male.

It wasn’t always so. Chris is the kind of kid who doesn’t like to be noticed, his mother, Jen, said. As a girl, he wore makeup, dressed in feminine clothing and went by his given name because that’s what was expected.

Things started to change as Chris approached puberty. First, he came out as a lesbian and then, a month later, as transgender.

“She felt more comfortable as a guy,” Jen said.

Now, Chris crops his hair, uses male pronouns and wears men’s clothes. He is taking medication to suppress menstruation because his period is emotionally traumatic, Jen said.

Chris, from Collegeville, Pennsylvania, is one of 180,000 kids enrolled in the Pennsylvania Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). It is free for many low-income families, but is available at discounted rates for people who make a higher income yet struggle to pay their children’s coverage, like Chris’ parents.

But his subsidized insurance is in peril as the Pennsylvania House of Representatives weighs a bill to exclude transgender health care services from CHIP and Medical Assistance coverage.

House Bill 1933 would prohibit tax dollars from funding surgery, physician and counseling services, inpatient and outpatient hospital services and prescription drugs related to gender reassignment.

Local

Breaking news and the stories that matter to your neighborhood.

The language, written by Rep. Jesse Topper, a Republican who represents portions of Bedford and Franklin counties, goes further than previous attempts to limit subsidized health care for trans patients. Earlier versions of the bill merely limited CHIP coverage to exclude gender affirming surgery.

For Jen and her husband, health insurance already costs approximately $800 a month: nearly $200 for their three children’s CHIP coverage plus $600 for the parents’ private health insurance.

Chris’ coverage helps offset the cost of monthly counseling sessions at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Jen said. There, Chris and his siblings, plus Jen and her husband, undergo therapy sessions individually and as a family. The doctors want to ensure the five are adapting to Chris’ transition.

“I don’t know how we would be able to pay for it,” Jen said.

Topper introduced the proposal last month after similar legislation was removed from the CHIP reauthorization bill. His was in response to a 2016 memo by the state Department of Human Services expanding coverage to include trans medical services.

“I wanted to have a public policy debate,” he said.

At the time of the DHS memo, the topic was never opened up to review by local lawmakers, he said.

Despite the attention by state lawmakers to trans services, only 34 CHIP recipients used their coverage in 2016 for behavioral or physical health services related to gender dysphoria, Department of Human Services (DHS) acting secretary Teresa Miller said.

She declined to give an exact tally for those who sought gender confirmation surgery, adding that “if a policy impacts fewer than 10 people, that’s when we don’t give numbers.”

“It’s a very difficult issue. It’s a very emotional issue,” Topper said. “I’m just trying to find out the most information as I can as we move forward.”

Currently, there is no overwhelming consensus on how best to treat trans children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics warns that without medical treatment or counseling, people diagnosed with gender dysphoria — a conflict between a person’s physical sex and the gender they identify with — risk developing behavioral and emotional problems, including psychiatric disorders.

Another group, the American College of Pediatricians, suggest trans kids would be better served by aligning their gender identity with their anatomic sex.

The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey by the National Center for Transgender Equality found that 40 percent of trans adults reported attempting suicide in their lifetime. More than 90 percent of those people said they made an attempt before the age of 25. Many of those respondents also reported higher instances of depression, abuse, homelessness and addiction.

Like many trans youth, Chris suffers from depression. He has contemplated suicide and was put into an inpatient program for 10 days. CHIP paid for that. CHIP also paid for ongoing counseling at CHOP and outpatient treatment at Deveraux Advanced Behavioral Health in Phoenixville.

“It saved my kid,” Jen said. “Without it, I don’t know how much money we would be in debt. I am forever grateful.”

Regardless of their age, people choosing to transition undergo a rigorous screening process that begins with medical and mental health professionals. They conduct psychological tests on patients to ensure someone is truly suffering from gender dysphoria, not a passing phase, according to doctors at Philadelphia’s Hahnemann University Hospital's Transgender Surgical Program.

Once a doctor and a family gives consent, a young enough patient could be eligible for hormones known as puberty blockers.

People who wish to continue transitioning may then undergo hormone therapy to receive more estrogen or testosterone. Gender reassignment surgery becomes an option when a patient has stopped developing. At Hahnemann, cosmetic procedures are not performed on people under the age of 16.

The cost of these procedures can be overwhelming for many families. Some worry that if CHIP coverage lapses for trans-related services, it could have a ripple effect on private insurance companies.

When 9-year-old Zurie of West Philadelphia first showed signs of being trans, her family was cautious. Her mother, Amy, initially balked when her son asked to wear a My Little Pony T-shirt. At first, Amy only allowed him to wear it inside the house. She then put the shirt in the dirty laundry and eventually made it disappear.

Zurie persisted.

“I don’t feel like it’s a choice for her,” Amy said. “She did get a choice about transitioning and expressing herself, but she didn’t get a choice about this innate sense that she is a girl.”

Zurie’s transition, for now, is mostly a matter of changing her name and haircut. Even Amy’s private insurer agreed to change Zurie’s gender identity in their records.

Over time, Amy has come to accept that her daughter knew herself better than anyone else. The question of whether her son was old enough to understand the concept of gender vanished and a daughter rose in its wake.

Yet one of Rep. Topper’s sticking points in writing his bill is that gender affirming treatment is a personal preference and should not be subsidized by the government. In a statement, he called gender affirming surgery “not medically necessary and, in many cases, very harmful.”

Parents like Harvey, from Wynnewood disagree.

“There is a misconception that gender reassignment is elective, but it’s not, really, because the reason behind it is mental health,” Harvey, a father from Wynnewood, said. “To deny them is abusive.”

Harvey’s daughter, Maya, was 2 years old when she declared herself a girl. Her parents thought it was a phase at first, but then started to sense something was different about their son.

Maya didn’t exhibit the kinds of traditionally masculine traits that were so obvious in her brothers. She wanted long hair parted in pigtails. She asked to paint her nails.

“When she turned 4, it really escalated,” her father said. “She asked why God made her a boy.”

Last year, Maya’s family had their first brush with bias after relocating to Memphis, Tennessee, for Harvey’s work. They bought a house, found a school and alerted the headmaster to Maya’s gender preference. Things fell apart shortly after arriving in their new home, Harvey said.

Maya’s school threatened to rescind her acceptance. The administration suggested introducing a PTSD expert for students disturbed by a trans child on campus. The headmaster called Maya a hermaphrodite, according to Harvey.

“It was eviscerating,” he said.

The family didn’t last long in Tennessee. Harvey’s wife, Jamie, packed up their children and returned to Wynnewood. Harvey sold his new house and slept in his office for months until he was able to join his family. The experience left them shaken and worried for what could happen next.

With that in mind, Harvey and Jamie consulted a financial advisor shortly after Maya’s revelation. They were told they should save an amount of money equal to a year’s tuition at a private college to have enough for future gender-affirming medication and procedures.

“The reason we do this is because we want them to be healthy and happy,” Jamie said.

Maya will enter puberty in a few years and the family will be forced to decide what additional phases of transition, if any, to pursue. The question of how to pay for it is never far behind.

“The risks of not taking [gender affirming] medication is that my child would become so depressed she would kill herself,” Harvey said.

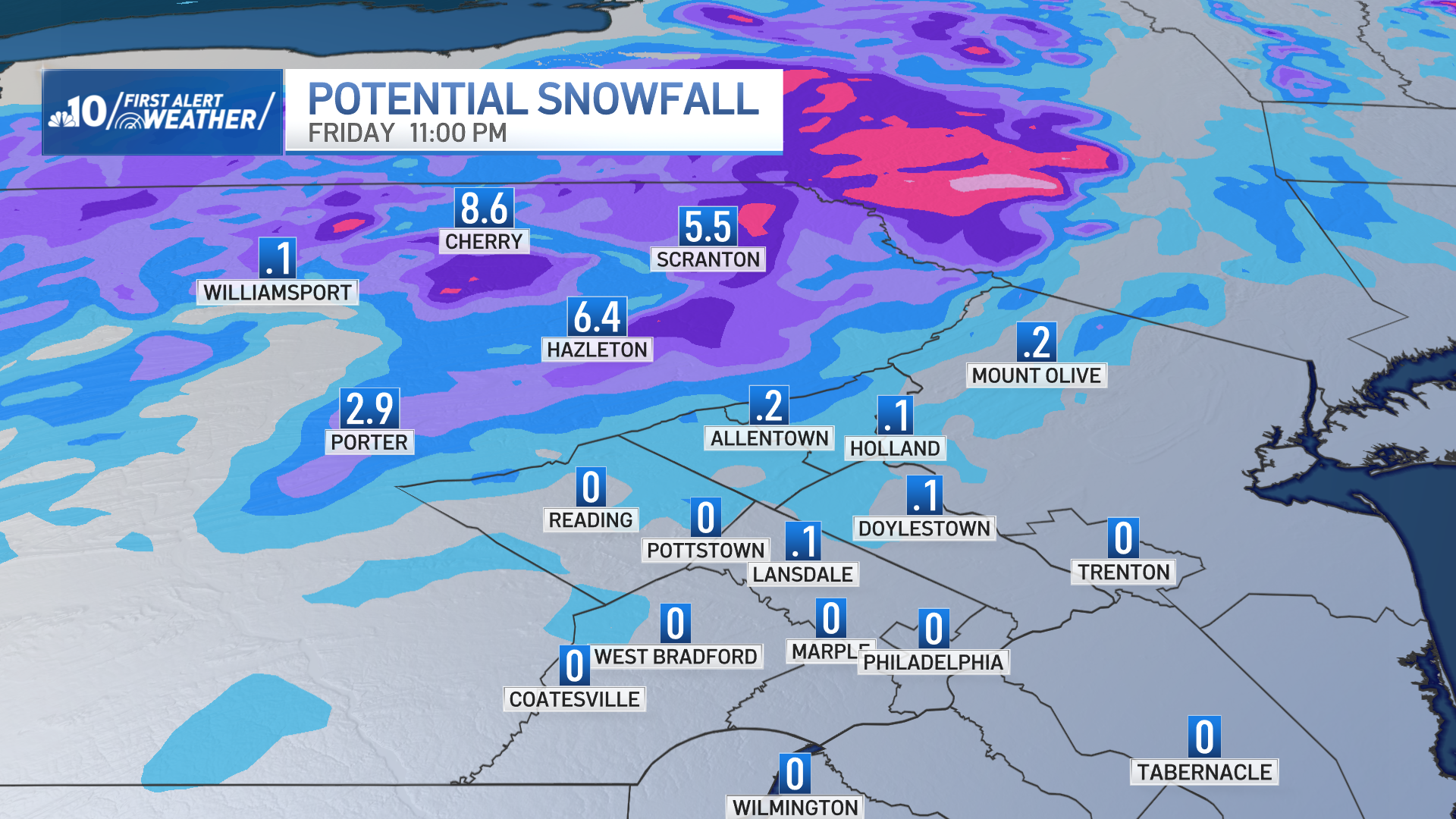

The federal government funds nearly 90 percent of Pennsylvania's CHIP program. Currently, the program has enough money to operate through early February, according to DHS. It could cease to exist without a renewed promise from federal lawmakers.

With just two weeks until the deadline runs out, Gov. Tom Wolf on Tuesday joined 11 other governors from both parties in writing a letter to Congress urging lawmakers to authorize CHIP funds before recipients lose their coverage.

"I’m joining bipartisan governors to insist that Congress stop putting our kids on the backburner and reauthorize funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program," he said on Twitter.

State Rep. Madeleine Dean, a Democrat who represents Montgomery County and is running for lieutenant governor, has introduced counter legislation to Topper’s bill. The Taxpayer Protection of Gender and Sex Reassignment Services Act would guarantee all CHIP and Medicaid recipients receive federal aid for trans care.

“This is not something that has great fiscal impact,” Dean said. “This is something born from ideology. It is certainly not something of science.”

The point is not lost on current CHIP recipients, like Chris’ family.

“I don’t fight to get [breast augmentation] for Chris,” his mom said. “I fight to keep him alive.”