If the plan was for the School District of Philadelphia’s board members to approve the adoption of a hybrid reopening model Thursday night, then that plan failed miserably after marathon public comments from concerned parents and teachers.

The board meeting began Thursday afternoon and stretched past midnight into Friday morning as parent after parent and teacher after teacher voiced safety fears over having in-person classes, even if only for two days out of the week. By the end of it all, the school board acquiesced to Superintendent William Hite’s request that the district be given another week to modify its reopening guidance.

Much of the concerns voiced Thursday night centered around the risk of spreading the virus in the confines of a classroom, as well as a lack of a baseline number of COVID-19 cases in schools which would force their closure.

“How many deaths of students and our staff will you find acceptable?” Olivia Jones, the assistant principal at John Marshall Elementary School, asked board members. “I am the caregiver of two young children and a disabled spouse. Who will care for me if I become sick? What insignificant words will you tell my family if I die?”

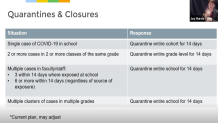

Dr. Thomas Farley, the city health commissioner, whose department helped craft the district’s plan, said that to determine whether to shutter schools again, the city would monitor for clusters of infections of students or staff in multiple schools, as well as rising community rates and links between school cases and community cases.

However, he acknowledged that no set number of cases has been established that would trigger closures, and both he and Hite have conceded in the past few weeks that there would likely be infections within Philadelphia’s schools.

City Council member Helen Gym pointed to the plan's reliance on individual schools and families to self-screen for coronavirus symptoms as a potential problem, with Farley admitting that the health department would not be able to assess how closely individual schools are adhering to health guidance.

“Just to be clear, we will not be monitoring implementation of the safety measures at the school level. There’s too many schools; we don’t have the staff to do that," he said.

Still, Dr. Stacey Kallem, a pediatrician and director of the health department’s division of maternal, child and family health, said that in crafting the plan the department considered the relatively low number of infections involving kids.

Of all the cases in Philadelphia, only 1% were in children between 5 and 11 years old, she said. Children 2 to 18 years old made up 2% of cases. There is also evidence that kids may transmit the virus less frequently than adults do, Kallem said, though she acknowledged that the research is “mixed.”

Farley and Hite pointed to concerns about student learning as they continued to advocate for at least a limited amount of in-person instruction.

“We do think that in-person education has a higher quality than digital education, and we do have quite a bit of concern that if children fall behind on their education during crucial years, they may never catch up and the consequences of that are life-long,” Farley said.

For his part, Hite noted that, “Now we know based on evidence and research that children from circumstances of poverty, particularly Black and Latino children, were disproportionately impacted with going to a virtual learning type of approach.”

Black and Latino children represent 73% of the district's more than 200,000 students. The district is the eighth-largest in the nation and the largest in Pennsylvania.

The superintendent added that the longer schools forego in-person instruction, the more kids may fall behind, especially those with special needs and English learners.

Parents, though, did not seem convinced.

Pat Kingsley, whose son and daughter attend school in the city, noted that the virus spreads through close and prolonged contact, especially indoors – conditions that are unavoidable in a classroom setting.

“This is a life and death decision,” he said.

Claire Murphy said she was initially looking forward to having her rising kindergartener attend in-person classes, but has since changed her mind.

“We’ve been very involved with the school and planned on her starting this fall, but now we just don’t think that it’s safe for children, teachers or household members,” she said.

Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, called a plan to provide educators with just one complementary mask for the semester “insulting."

“PFT members want to be in schools supporting our students face to-face as long as it is safe, and that’s not selfish; it’s human,” he said. “But students and staff cannot be asked to jeopardize their lives and the lives of their families by passively accepting a plan that is, as it is currently written, entirely insufficient and lacks absolutely non-negotiable safeguards.”

Masks are also an issue for children getting to school via SEPTA.

Board member Julia Danzy wanted to know what the transit agency was doing to encourage mask wearing and social distancing. Scott Sauer, the agency’s assistant general manager, said SEPTA will be deploying “social distance coaches” at its stations to encourage proper mask wearing and social distancing, but he admitted that the agency’s mask requirement is largely unenforceable.

“Our operators will advise [riders] of the need for a mask, encourage mask use, but we don’t want to put our operators in a position to enforce mask-wearing,” he said.

Parents, teachers and principals also criticized the “hypocrisy” of officials holding virtual meetings to prevent getting infected, all the while advocating a learning model that would expose students and school employees.

They noted that the district first closed schools back in March, when there were far fewer infections than there are now, and argued that the time spent crafting a policy for hybrid learning could be better spent training teachers on how to adequately and effectively provide digital instruction.

Philadelphia schools are not unique as they try to craft plans for fall instruction. The Los Angeles Unified School District, the second-largest in the country, has already announced that it will begin the term fully online. Other districts have done the same, too.

And in a sharp reversal, President Donald Trump on Thursday conceded that some school districts will not be able to begin in-person classes right away. The Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention similarly recommended digital learning in areas where viral spread is prominent.

After all the withering criticism, Hite said that the district would attempt to modify its plan. The lack of a vote by the school board, though, is a setback, since under state guidelines, board approval is needed before schools can begin in-person classes.

The board is now set to vote on the modified plan next week.