Her voice cracks as she pleads for help. She’s locked up with nowhere to go, and she knows that inside this Philadelphia prison, the coronavirus has begun to spread – and she may be its next victim.

“I’m a mother of five and a grandmother of four and I already have complications. I don’t want to die in here," she wails. "I know what crimes I’ve committed, but my crime doesn’t carry a sentence of a death penalty.”

The woman’s pleas can be heard in an audio recording from inside the Riverside Correctional Facility, which houses the city’s female inmates. The audio was released by the Philadelphia Community Bail Fund, which advocates for an end to cash bail and posts bail for some prisoners.

To slow the spread of the deadly new strain of coronavirus, medical experts have urged people to avoid close contact. But behind bars, where close contact is unavoidable, the virus is spreading and creating a crisis that advocates say is endangering lives, both inside and outside jail cells.

They believe the crisis can only be alleviated by releasing some offenders.

“The problems that we’re seeing in jail are the problems that we’re seeing in the community, only times 10,” said Claire Schubik-Richards, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society.

Her group represents Pennsylvania prison inmates and advocates for their humane treatment. Schubik-Richards said the city’s jails have better medical care than others in the state, and she praised the decision to increase the number of free minutes that inmates have been granted during phone calls.

But, Schubik-Richards said, Philadelphia is still being hampered by a scattershot approach at both the local and state level.

“The problems that we’re seeing in jail are the problems that we’re seeing in the community, only times 10."

Claire Schubik-Richards

Gov. Tom Wolf's administration has expressed an interest in releasing some inmates from state prisons. On Friday, he authorized the release of as many as 1,800 of them.

But that doesn't affect local institutions.

The Pennsylvania Prison Society tried to get each judicial district to quickly reduce the number of people in jail, filing a petition with the state Supreme Court, but that petition was denied.

In Philadelphia, District Attorney Larry Krasner and the city’s Defender Association compiled a list of nearly 2,000 people who they determined should be considered for release by the First Judicial District court.

Krasner said his office and that of the public defenders association had been trying to work on a solution with First Judicial District leadership since early March.

He expressed concern about how long it took for leadership to take action, but said he was heartened that judges this week began considering more cases under a “streamlined process” involving virtual court hearings. On Tuesday, he said, there were hearings for 120 inmates, and that number grew Wednesday and Thursday.

“We look forward to more progress next week,” Krasner said.

Cara Tratner, an organizer with the Philadelphia Community Bail Fund, said the First Judicial District courts should have been doing more sooner, and believes Mayor Jim Kenney should also take action.

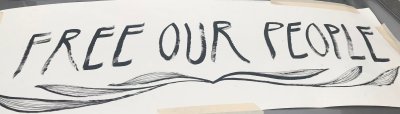

Her group protested in front of City Hall Friday, calling on Kenney and the First Judicial District to immediately release some prisoners.

Kenney’s office said it cannot grant prisoner releases unless ordered to do so by the district court, but Tratner said he should at least be using his bully pulpit to advocate for more prisoner releases.

“They waited way too long and they should be doing way more. The cases have already spread rapidly,” she said.

The First Judicial District did not return a request for comment.

Meanwhile, the virus had infected at least 71 inmates as of April 10, according to a city spokesperson. Though the city has reported no deaths among inmates, fear and anxiety are gripping both those locked inside and their families outside.

Luz Acevedo was recently released from the Riverside Correctional Facility thanks to the help of the Philadelphia Community Bail Fund. She served three months on drug charges and described a sense of uncertainty inside the jail.

"We look at each other from cell to cell as if to say, ‘We’re going to die. We may die.’"

Luz Acevedo

“It’s sad. We look at each other from cell to cell as if to say, ‘We’re going to die. We may die.’ We don’t really know what’s happening,” she said.

The city's jails have been under "shelter in place" status, a city spokesperson said, with a limited number of inmates being let out only a half hour a day to shower and make phone calls. Inmates who test positive are put in single cells in isolation housing units, with their prior cellmates being "quarantined and monitored for symptoms."

"It's depressing," Acevedo said.

To try and lift each others’ spirits, inmates blow kisses at one another, she said. But blowing kisses can only do so much.

Acevedo’s mother and children are in Puerto Rico. While talking to them from inside jail, she would do her best to not worry them. She told them to remember that she loved them, in case anything happened to her, she said, her voice straining to hold back tears.

Roget Walker has a sister in the same jail. With visits currently banned across the city’s prison system, Walker worries about what may happen to that sister, who suffers from underlying physical and mental health conditions.

“My sister can die. She has health problems and this stuff attacks people with health problems. It’s just scary. She’s not dead, but I feel like she can go any day,” Walker said.

Walker feels ignored by prison officials, and she said more information should be provided to families.

Despite providing infection numbers for inmates, the city has been somewhat tight-lipped about the virus inside its jails. NBC10 tried to contact the Philadelphia Department of Prisons’ medical operations chief but were referred back to the city’s press office.

Citing privacy concerns, a spokesperson for the city said they’re not revealing how many corrections officers have been infected, noting only that none have died. They also refuse to say if the virus is being passed from corrections officers to inmates, and vice versa.

“We’re not commenting further on how infections have spread, other than to say that we are doing everything possible to mitigate the spread within PDP," the city told NBC10 via email.

But both Schubik-Richards and Krasner said it’s impossible to believe that inmate-to-corrections officer transmission has not occurred. They cited this as a reason to release more inmates, saying that infections can pass to corrections officers and then from corrections officers to their families and others on the outside.

“This is and always has been about keeping all of society safe. We don’t have to be knuckleheads about this and pretend that somehow those corrections officers, when they go into that jail, are going to come out unscathed,” Krasner said.

Eric Hill, business agent for Local 159, told NBC10 partner KYW News Radio that his union members are worried about the lack of information coming from city officials, and they fear the personal protective equipment granted to them is inadequate.

“They are nervous,” Hill told KYW. “I get dozens of calls a day. In fact, my phone starts ringing at 4 a.m.”

Thus far, the city said the prison population stood at 4,203 inmates as of April 9, a net decrease of 532 inmates since March 16. Schubik-Richards said the city’s inmate reduction compares unfavorably to that over other counties.

Acevedo, the former inmate, said she fears the consequences of inaction.

“We’re not perfect. We make errors and we have faults,” she said. “Life hits us hard, sometimes because of our own actions and sometimes because of others, but we need to survive. We can’t die abandoned.”