Johnson & Johnson's vaccine became the 12th vaccine worldwide to gain approval, and the third in the United States to gain emergency authorization use on Americans seeking vaccination.

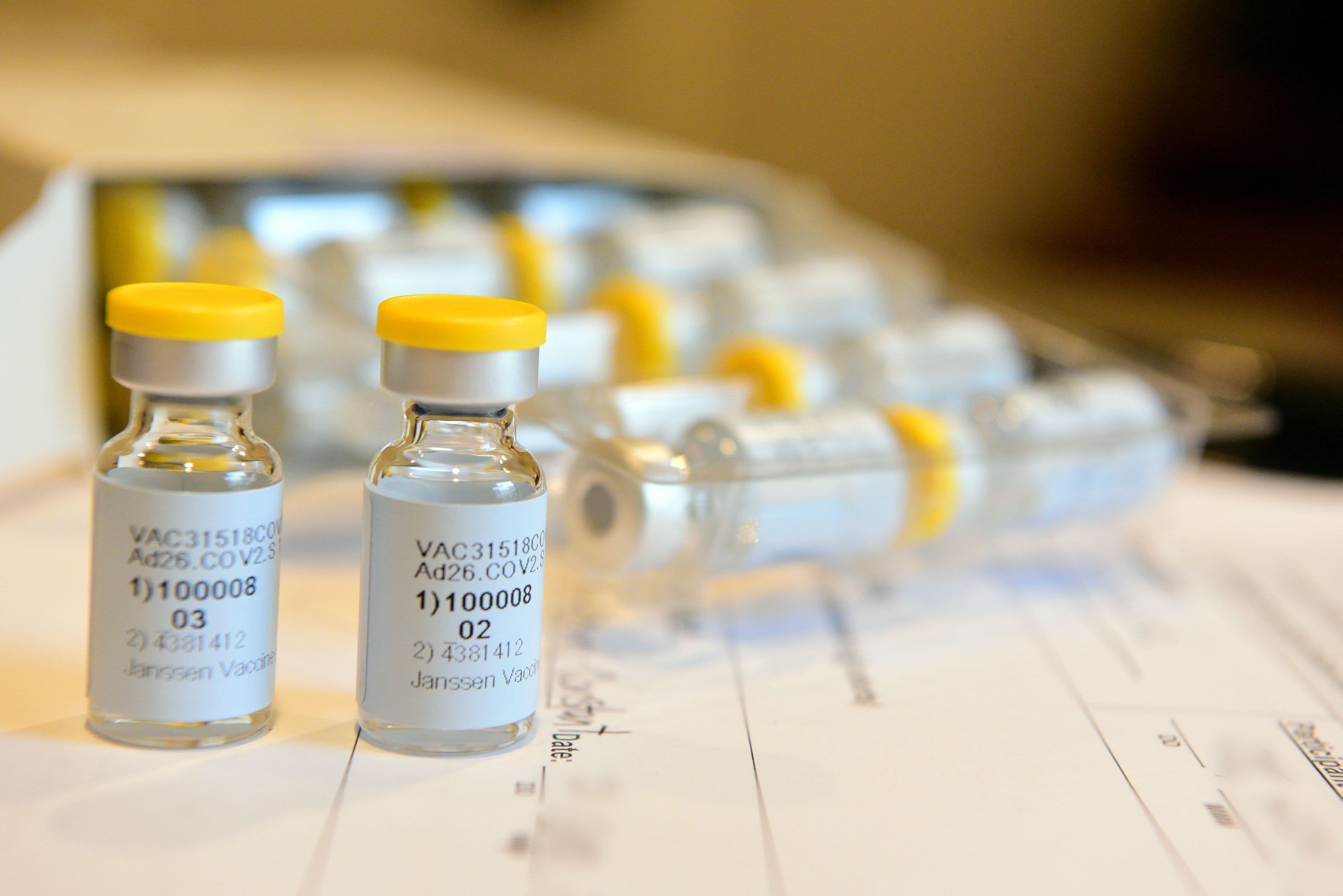

Unlike the other two already approved in the U.S., the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the J&J "Janssen adenovirus-replication-deficient COVID-19 vaccine" only take one shot to gain effectiveness at holding off serious illness by the coronavirus.

The secret ingredient is the adenovirus, which is a virus that causes the common cold. However, in the vaccine, it has been "inactivated." More specifically, the adenovirus is called Adenovirus 26 and is of human origin, according to the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Other vaccines already being used in other counties, including the Sputnik 5 in Russia, already uses Adenovirus 26, CHOP said in a blog post about the new vaccine last month. Meanwhile, still other vaccines, like one currently being used in India, uses Adenovirus 5. (Sputnik 5 also uses Adenovirus 5 as well as Adenovirus 26.)

Get top local stories in Philly delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC Philadelphia's News Headlines newsletter.

Here's how the Adenovirus 26 is used in the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, according to J&J:

"It uses an adenovirus -- a type of virus that causes the common cold, which has been inactivated -- to carry a gene from the coronavirus into human cells. The cells then produce coronavirus proteins (not the virus itself) to mimic the virus, which helps prime the immune system to fight off later infection in the body encounters the coronavirus."

The J&J vaccine received emergency authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last weekend, and federal health officials said the expectation was to have 3-4 million doses of it sent to states this week.

A Pennsylvania health official told reporters Tuesday that the state has yet to receive any J&J doses. She declined to give more details at the press conference about the rollout of the new vaccine to counties throughout the state, saying only that more information about the new vaccine would be available "later this week."

The effectiveness of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is not as high as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, according to clinical trials. Those are roughly 95% and 85% effective against severe illness caused by the coronavirus.

J&J tested its single-dose option in 44,000 adults in the U.S., Latin America and South Africa. Different mutated versions of the virus are circulating in different countries, and the FDA analysis cautioned that it's not clear how well the vaccine works against each variant. But J&J previously announced the vaccine worked better in the U.S. -- 72% effective against moderate to severe COVID-19, compared with 66% in Latin America and 57% in South Africa.

While that efficacy rate is not as high as Pfizer's or Moderna's, it is still generally higher than the seasonal influenza vaccine, according to experts.

Some advocates for equality among those receiving the vaccine are hopeful the one-shot vaccine will allow for local pharmacies to get involved in the vaccination process and reach more communities.

Meanwhile, fellow pharmaceutical giant and J&J's rival, Merck, agreed in an unusual move to help Johnson and Johnson produce its vaccine. The agreement was facilitated by President Joe Biden's administration, and will help speed up the rollout of the vaccine.

50.7 million people, or 15.3% of the U.S. population, have received at lease one dose of a coronavirus vaccine, according to the CDC, while 25.5 million people have completed their vaccination, or 7.7% of the population.

According to data through March 1 from the COVID Tracking Project, the seven-day rolling positivity rate for testing in the U.S. went from 5.6 on Feb. 15 to 4.4 on Monday.

The Associated Press contributed reporting to this story.